"Next!"

The woman in a white nurse’s uniform bellowed, ushering the next person in the queue forward.

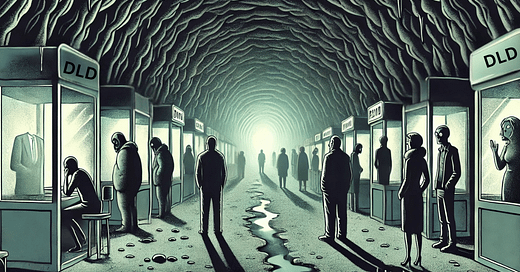

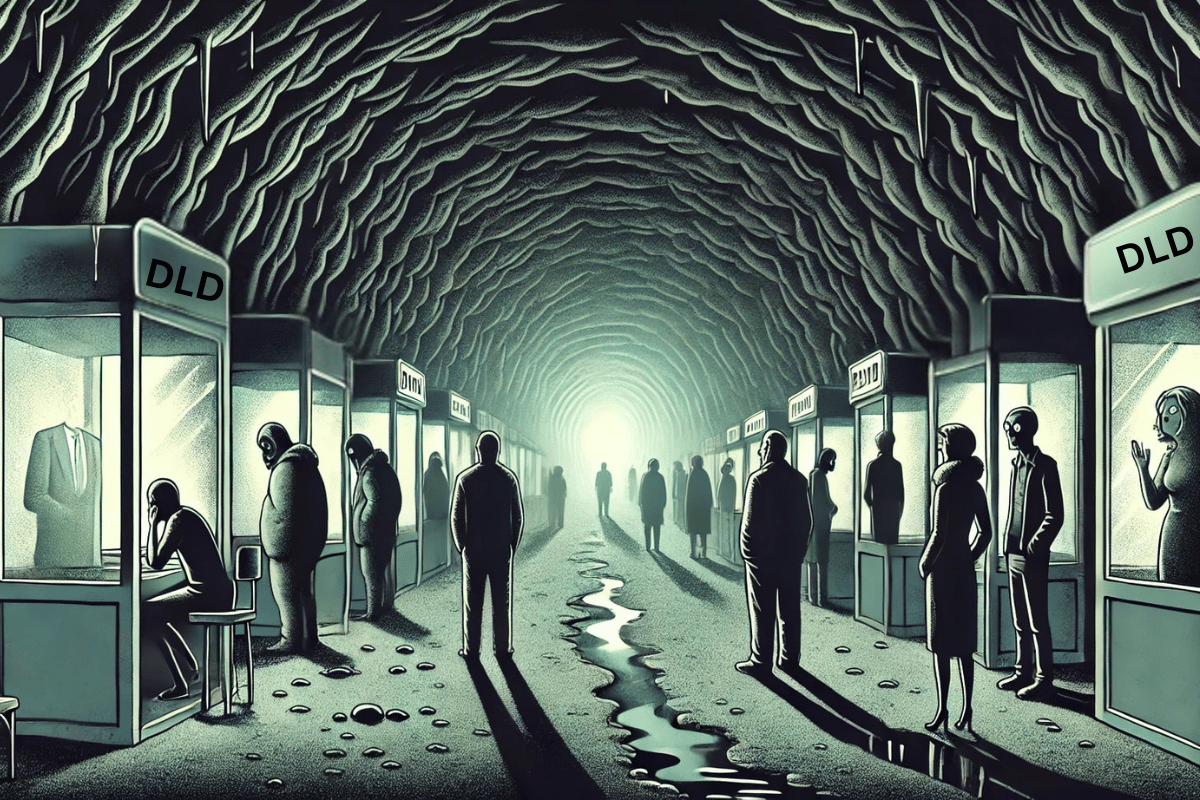

Fred was number 1,199,999, and his ticket was the size of his hand, just so all the digits could fit. The drab waiting room was filled with hundreds of people curled up on wooden benches as if they had already died and their souls were waiting to be collected from the station.

"Name and age, please," she said without looking up, continuing to type on her keyboard behind the glass partition.

"Fred Peterson, 22."

She still didn’t lift her head. "So, what’s wrong with you?"

"Oh, I’m terminal. I’ll probably go this year," he said, completely matter-of-fact.

Her face brightened. The droop on one side of her mouth curved upwards at this information. He figured he must have been the first terminal case of the day.

"Okay, well, you’re actually lucky because we can give you a choice—you’ve just made the cut-off age."

Fred had turned 22 three weeks ago, allowing him the privilege of receiving a small sum to survive on.

"Would you like a lower rate of benefits—since there’s no point in giving you the full amount—or would you prefer a special package to ease your pain?" she asked, her voice perking up at the end.

"Can you tell me more about the package?" He had heard about these new pods, but he’d never seen a picture of one before. Apparently, the government was still trialling them, testing them on a few pensioners before rolling them out to the infirm.

"Right this way, sir." She smiled, almost bouncing with glee as she led him to another room. It was the first time he had ever seen a Department of Life and Death (DLD) worker so upbeat. Usually, they would hound you with questions, hoping you’d lose the will to live before completing the process. Perhaps that was why they were called the DLD.

The white room looked vastly different from the waiting area. While still sterile, it had an ethereal glow, like a spa. The entire back wall featured a mural of a beach scene—crystal-blue waters, golden sands, the whole shebang. The sound of waves and distant parrots played softly over hidden speakers.

She gestured towards a padded seat in front of a desk. Practically beaming, the nurse showed him a range of pods on her computer.

The first looked like a giant, futuristic egg with windows. Another was dome-shaped, reminiscent of the Eden Project, which housed thousands of plant species in an enclosure designed to mimic a natural biome. It felt comforting and familiar.

"Before I choose, can you tell me how it happens? Who’s going to be there, etcetera?" he asked.

"Oh, right. Give me a second." She fumbled with her desk drawers and pulled out a gigantic binder—one that rivalled Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, which was ironic, given that he had very little left.

Licking her thumb, she flipped through the pages and read aloud: "The person’s choice must be approved by two independent doctors and a high court judge—oh wait, sorry, that’s an old version." She spun around and typed into Google: Assisted Dying Bill.

"Oh, that’s right. It’s now two independent doctors and a panel."

He frowned. "A panel of what? Glass?"

She stopped smiling.

"Look, I’m trying to help you. It says a panel of assisted dying experts," she said, as if that explained everything.

"Okay… and who are these experts?" He smirked, amused by her growing unease.

"Let me see. Oh, here we go. It’s a three-person panel comprising a senior legal figure, a psychiatrist, and a social worker, who oversee applications."

He grumbled under his breath.

"But you do need to have the mental capacity to make the choice. Let me just check—do you have about six months to live?"

Fred slumped back in his seat, folding his arms. "Something like that."

"Great!" she said, the twinkle returning to her eyes.

He wryly ventured, "So, what are they planning to do? Hanging? Firing squad? Electric chair?"

The nurse huffed.

"Mr Peterson, if you’re not going to take this seriously, I’m going to have to ask you to leave." She pointed to a sign that read:

"We will not tolerate threatening, abusive or violent behaviour. Under these circumstances, no member of staff should be required to, or feel obliged to, deal with any customer, whether face to face, over the phone, or in correspondence."

She looked triumphant, spreading her arms across the desk as if asserting her authority.

"Well, what’s the alternative? Realistically, how much will I get for the next six months?" he asked.

The wrinkles around her eyes and forehead tensed. Fred could tell she wouldn’t have invited him to this exclusive zone if she had known he was going to ask about benefits. He would have been turfed out like the rest of the plebs.

"Well, it’s around £416.19 per month in support. And the Limited Capability for Work-Related Activity support is now £50 per week," she said in a monotone, crossing her arms.

"It’s not a great quality of life, Mr Peterson."

Fred pinched the bridge of his nose. "Okay. Say I go ahead with this—what are they actually going to do to me?"

"The doctor will administer an approved substance. We can’t tell you what it is, just in case you go and make it at home," she said in the most serious voice possible.

Fred laughed, thinking she was joking. "If I’m going to die, why does it matter who does it? They might as well give me the recipe. I mean, I’m a terrible cook, but I’m sure I can inject a load of crap into myself."

"Well, a lot of people don’t get it right and end up even sicker," she said.

He caught on. More sick people meant more people on benefits. If you do it once, do it right.

"Wait," he interjected. "That still doesn’t explain why there’s an egg and a dome. What the hell have they got to do with anything?"

She perked up again. "Oh! We want to make sure the last thing you see is pleasant."

Fred felt like he was on a rollercoaster with this one. Maybe she was undiagnosed or something? Either way, it wasn’t like she’d be entitled to anything. Suddenly, he felt very sorry for her.

"Fine, fine. Sign me up for the dome thing," he relented.

She almost jumped up from her seat. "That’s great! I’m just going to fill in this online form," she said, turning away. From the side, he saw her tick the option referral fee, and he wondered how much commission she was getting for this.

The clickety-clack of the keyboard continued as he surveyed the room. A faint lavender scent hung in the air, and he hoped that would be the last thing he ever smelled.

She spun to face him as if about to hand him a receipt.

"One more thing we wanted to check before you…" she said, gulping.

"In the meantime, how would you feel about trying to return to work?"

Copyright © 2025 Suswati Basu. All rights reserved.

Lol, the final line about going back to work--that was rich! It started out with a bang in the waiting room ...'as if they had already died and their souls were waiting to be collected from the station.' I laughed out loud. What is normally a touchy subject for some people--this was handled with humor. Loved it. You are my 252nd bedtime story in this story circle :)

That's a horrifying vision of where, I think, we're ultimately heading. The scary part isn't even so much people wanting to die as how others can be so cheerful about the whole process while trying to squeeze the remaining juice out of a person before they pass away. But then again, reality is just a collective reflection of our inner lives, after all.

Loved the attention to detail, too. Thanks for posting this!